Leeds Beckett University - City Campus,

Woodhouse Lane,

LS1 3HE

Can Neuroscience Explain Human Experience?

In this post, Leeds Metropolitan University psychology expert Dr Steve Taylor, explains how the need to explanation leads to quasi-religion

Human beings have always had a strong need to make sense of the world around them. This was undoubtedly part of (although by no means the only) the original function of religions. In non-theistic cultures, spirits were the causal agents—diseases were caused when ‘evil spirits’ entered the human body, while changes in the weather were caused spirits of the wind or the rain. In theistic cultures, Gods (in the singular or plural) were responsible. Even if they didn’t directly cause events, people became ill, had accidents, died and became pregnant because it was ‘God’s will.’

For many people, these divine explanations have been superseded by science. We now have a much more rational understanding of how the world works, which is perhaps one of the reasons why;religion no longer has such a central role in our culture.

However, even in modern science, it’s easy to see the same impulse for certainty at work, grasping at potential ‘explanatory material’ and creating connections when none may be there. There is a quasi-religious need to build up an ‘explanatory structure’, which often inflates and distorts evidence.

Until recently, the main explanatory tool was genes. In 2000, geneticists were in the process of mapping the ‘human genome,’ in the hope that the genes responsible for the whole spectrum of human experience would be identified. (Sometimes the genome was referred to as ‘the book of life.’) There was a hope that this would lead to a revolution in our understanding of everything from disease to human consciousness. These were the ‘gene for’ years, when it was presumed that there was a genetic explanation for everything. Genes (or at least genetic processes) made people religious, criminal, gay, psychopathic, alcoholic, intelligent, depressive...

But the genome project was a disappointment. It threw up more questions than it answered, and revealed that genes are much less significant than thought. It found that human beings only have around 23,000 genes, much less than expected - only half as many as a tomato. The genetic map does not show what makes human beings different from other animals (such as chimpanzees). We have also learned, surprisingly, that inheritable characteristics such as height are only very slightly related to genes. There are no ‘genes for’ after all. We have also found that most common diseases do not appear to have a genetic basis, so that the project has not led to significant medical benefits, as many believed it would. As Jonathan Latham, director of the Bioscience Resource Project, puts it, "Faulty genes rarely cause, or even mildly predispose us, to disease, and as a consequence the science of human genetics is in deep crisis."

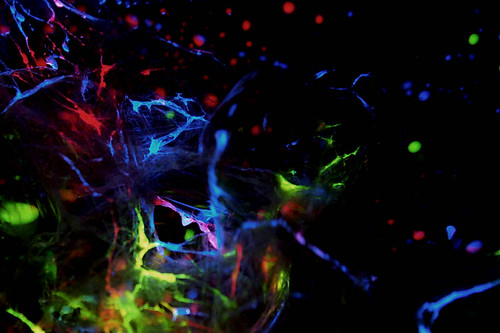

Neuroscience as an Explanatory Tool

Now, as a result, the explanatory emphasis has shifted away from the genome, up to the human brain. Neuroscience is the latest explanatory fad. It’s no longer genes which are responsible for everything, but "neuronal circuits." Neuroscientists have claimed to identify the brain activity—or the parts of the brain—associated with terrorism, creativity, aesthetic appreciation, political affiliation (Republicans have different patterns of neurological activity to Democrats) and a host of other characteristics. And of course, a causal connection is usually made here. A particular pattern of neurological activity ‘causes’ terrorism, so that in theory one could ‘cure’ terrorists by changing these patterns, perhaps via neurosurgery or by means of drugs.

But just as with genes, there are major problems with explaining human experience in terms of brain activity. Firstly, correlation does not mean cause. Just because certain parts of the brain are more active when I read a poem or stare at a beautiful sunset, it doesn’t mean that the brain activity is responsible for the sense of beauty or wonder I experience. You could just as easily say that the feeling of wonder comes first, and ‘causes’ changes in brain activity.

There are also major problems with the assumption that brain activity can produce any type of subjective experience. Despite decades of intensive research and theorizing, no scientist or philosopher has come any where near close to explaining how the brain might be able to do this. In the field of Consciousness Studies, this is known as the ‘hard problem’ of how the soggy gray lump of matter we know as the brain can produce the richness of conscious experience. As the philosopher Colin McGinn puts it, to even assume that this is possible is tantamount to believing that water can turn into wine.

Finally, there are very serious practical problems with identifying the neurological activity associated with different characteristics. Most of the information we glean about brain processes is based on brain scanning technology, such as fMRI. When it comes to the brain activity, fMRI scanning is much less reliable and clearcut than many people realize. It doesn’t directly measure brain activity, only increased blood flow to the brain. There may well be important neuronal activity which doesn’t produce increased blood flow, perhaps from neurons which are acting more efficiently than others. FMRI scanning also makes it easy to forget that the brain’s activity is normally widely distributed than localized, depending on many different networks spread over the whole brain. It is absurd to attempt to pinpoint a particular part of the brain associated with a particular emotion or behavior.

In addition, to detect unusual types of brain activity, you have to know first what the normal pattern of activity is - which is very difficult to ascertain. One person’s ‘normal’ brain functioning may be different to another person’s. And finally, brain scans are vulnerable to bias and positive interpretation. It’s easy for researchers to interpret them in a way which supports their intentions. When different neuroscientists were sent the same image and asked to ‘unpick’ it, they responded with widely varying interpretations. As New Scientist magazine has admitted, "The reliability of fMRI scanning is not high compared to other scientific measures."

Accepting Uncertainty

I have no doubt that neurological explanations of human experience will prove as inadequate as genetic explanations. Perhaps the real question we need to answer is why we have such a strong impulse for certainty and understanding, and are so ready to create explanatory frameworks.

I suspect that the need to explain everything is rooted in a sense of insecurity, which creates a need for control. The world is chaotic and sometimes overwhelming, life is uncertain and contingent - and we’re just in here, conscious entities apparently trapped inside our own heads, forced to face up to the enormity of reality. So it’s important for us to create an explanatory framework to provide us with some security. In this sense, we’re not so different from our ancestors, who used spirits and gods as explanatory tools.

Perhaps, however, we should accept that there are some things we will never be able to explain. It would be more humble and sensible for us to accept that there are limitations to our intelligence and our awareness. And then, perhaps, we could learn to accept and even love the incomprehensible strangeness and randomness of life.

Dr Steve Taylor

Dr. Steve Taylor teaches on the Social Psychology BA and Interdisciplinary Psychology MA. His interests include Consciousness Studies, Spirituality, Positive Psychology and Transpersonal Psychology. He is the author of many best-selling books on psychology and spirituality.